Roman Kourion

Cypriot History

Roman Kourion (c. 50 BC – AD 500)

Cyprus was annexed by Rome in 58 BC after complex political and diplomatic wrangling between the Roman Senate and the Ptolemaic kingdom. After a generation of financial and personal mis-administration by Roman officials, followed by the tense civil wars between Pompey, Caesar, Mark Antony, Cleopatra and Augustus, the island settled down to become an essentially peaceful Roman province. While the island had been of great strategic value to its Ptolemaic rulers, its military importance ceased once the limits of the Roman empire were stabilised well to the east in Syria, hence its administration by the Roman Senate rather than by the emperor. Cyprus settled down to become a prosperous and, with a few exceptions, largely quiescent province under the Pax Romana.

Roman Cyprus is often described as a backwater because of its uneventful political history, but this very factor allowed the island to develop into the type of province the military machine of the Roman empire was designed to encourage and protect: a world of peaceful, prosperous, semi-autonomous communities, whose leading citizens competed with each other for the honour of serving their cities with benefactions and public services.

Limited historical sources make it difficult to determine how active the community of Kourion was in pursuing the sort of activities typical of their contemporaries in other provinces of the empire. Surviving epigraphic records suggest that it was in fact little different from other communities of the island or many parts of the eastern Roman empire. It should be noted, however, that the relative neglect of the Roman period on Cyprus has resulted in a rather impressionistic picture of the island, with little detailed attention to the rich archaeological record, despite the abundance of surviving monuments in most of the major sites, including Kourion itself.

The large body of inscriptions from this period demonstrate the typical operation of civic life, but also put the town in its wider imperial context. Emperors such as Nero, Trajan or Hadrian, the proconsuls, as well as local officials, priests and worthies, dedicated numerous offerings in the sanctuaries, especially the shrine of Apollo Hylates (‘of the woodland’) which enjoyed something of an international reputation in Roman times. The inscriptions also record the cosmopolitan nature of the population, with officials and traders drawn from other parts of the empire. These included Jewish elements, in the form of the cult of Hypsistos (‘Almighty’), which combined Graeco-Roman and Judaic elements. This influence has also been detected at the nearby town of Amathus, where curses written on lead and selenite (gypsum) tablets may reflect Jewish magical traditions, though of a kind familiar throughout the empire.

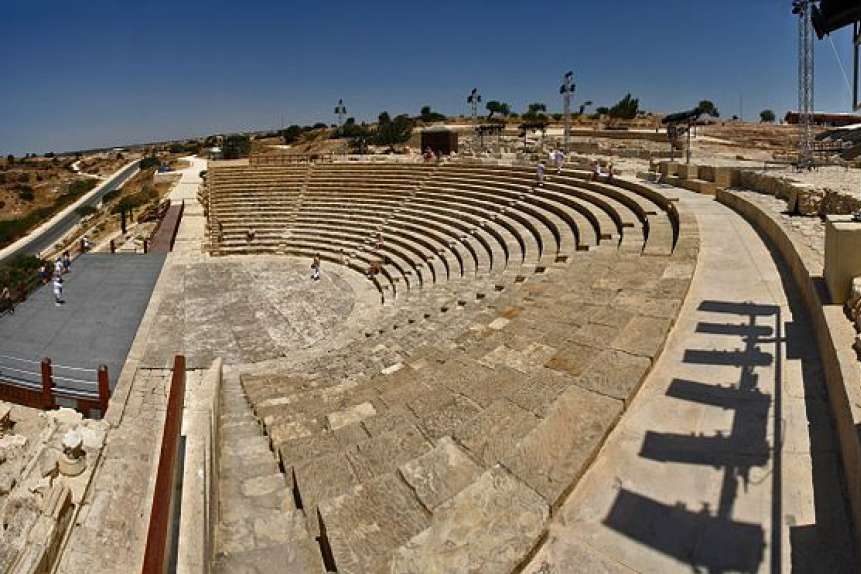

Excavations by the Department of Antiquities on the acropolis have also revealed much evidence of this prosperity. The theatre was extended several times, reaching its greatest extent under Trajan (AD 98–117) when it could have accommodated around 3,000–4,000 people. Remains of the agora, at least one side of which was surrounded by a monumental stoa, date from the same time in the second century AD. An impressive Nymphaeum, which also functioned as the major source of water for the centre of the city, is one of the largest of its type known in the eastern Mediterranean. Several adjacent buildings, such as the House of the Gladiators and the House of the Achilles Mosaic, are renowned for their finely executed mosaic decoration. Finally, a large stadium of Antonine date at the locality still called At Meydan (‘racecourse’) outside the city completes the picture of a typical city of the eastern Roman empire.

The sanctuary of Apollo Hylates also witnessed major changes during Roman times and reached its most monumental and complex state. Both of the major deposits of votive offerings from the CA to Hellenistic phases of the site were created in the middle of the 1st century AD, suggesting the sacred space was being reorganised on a significant scale at this time. The first phase of the present temple of Apollo was erected during the reign of Augustus (27 BC–AD 14), while the structure was completed with its familiar portico of columns early in the reign of Trajan in AD 101. Trajan also paid for a large structure known as the South Building, probably used as a dormitory or storerooms. Buildings typical of sanctuaries throughout the empire, including a large bathhouse and a palaestra (sports centre), were also added to what was by now one of the main sanctuaries of the island and indeed of the eastern Mediterranean.

Reconstruction of the sanctuary of Apollo Hylates in the Roman period. The Temple of Apollo is at the top of the illustration, next to the much older Cypro-Archaic temenos. The main sacred area was surrounded by buildings serving the needs of pilgrims and the officials of the shrine. (Image kindly provided by Dr David Soren).

A single item from the sanctuary is known to have entered the British Museum collection, this fine gold necklace inlaid with garnets. It was purchased from Percy Christian in 1897, and is said to have come from here. If this provenance is correct, then it is possible that this was a personal item dedicated by a pilgrim in Roman times.

The complex was badly damaged in an earthquake in the middle of the 4th century AD, after which there is very little evidence for cult activity, though there are signs of decline even before this disaster. The rise of Christianity during this time would have discouraged the extensive reconstruction of the sanctuary, especially after the imperial edict of AD 395 closing the pagan temples. The town itself, perhaps weakened by economic decline and the impact of earlier seismic activity, was also devastated by earthquakes in the 4th century AD. Dramatic evidence for this has been revealed in the ruins of houses on the acropolis. Despite this setback, the town was eventually rebuilt, perhaps after a period of abandonment, but apparently thrived into Late Antiquity when the city was the seat of the local bishop, probably based in the fine Christian basilica on the acropolis. The location of the so-called extra-mural basilica close to the site of the Classical shrine where Demeter and Kore were once honoured may have been coincidental, but could reflect an accommodation of older cult places by the new religion.

Roman period, late 4th century AD

The town was finally abandoned some time in the 7th century, when a combination of economic decline and the threat from Arab raiders made the coastal areas less attractive for settlement. The population moved inland to the site of the modern village of Episkopi, whose name reflects the fact that the new settlement remained the centre of ecclesiastical administration. The humble jug from the Hake-Kitchener excavations in 1882 illustrated here must have been among the items in use in this final phase of the town, which had been occupied for well over a thousand years.

Burial customs

Few tombs of Roman date from the Kourion area have been published in detail. Both of the main types, chamber tombs with long entrance passages and simpler pit graves from the earth or bedrock, continued earlier Hellenistic types represented elsewhere on Cyprus at Amathus and Paphos (where numerous burials of this period have been discovered in recent years) but also from older excavations at Kontoura Trachonia, Tsambres and Apehendrika in the Karpas peninsula.[105] There is also much evidence to suggest that many older Hellenistic funeral vaults were commonly reused, often by the addition of new niches or side-chambers (loculi) though this is not always clear from the descriptions of the British Museum-excavated tombs.

As before, in chamber tombs the deceased were laid out on the floor of the chamber or loculus, sometimes on benches with headrests or within sarcophagi (stone coffins). Coffins were also made of clay or wood and often do not survive, especially from older excavations. Niches with arched roofs (called arcosolia) and in-built sarcophagi, which were cut into the walls of tomb chambers, became very common in the Roman period and especially around the Kourion area. As the accompanying pictures of the Amathus Gate and Akrotiri cemeteries show, these are sometimes the only parts of the tomb that have survived millennia of man-made and natural destruction. In addition, many tombs were provided with cylindrical tombstones (known as cippi), usually inscribed with just the name of the deceased and a simple farewell.

Tomb 113 of the British Museum excavations consisted of a large rectangular chamber 5.2 x 1.5m and 1.13m wide approached by a stepped passageway. Two large recesses between 2.1m and 2.4m long opened from the back wall, while smaller niches led off the side of the chamber. Both of these side-chambers contained a sarcophagus, though one also had a lead urn full of cremated bone. The finds recorded by Walters date the tomb to the 1st or 2nd century AD: many glass bottles and other vessels, decorated lamps, bronze coins, several spindle whorls, and a bronze mirror and spatula. An inscription cut above one of the stone coffins in the right-hand recess is an epitaph in Greek to Metrodoros son of Metonos.

Although rather neglected by earlier excavators and many modern scholars, simpler tombs for small numbers of burials, with little or no architectural elaboration, were also very common in Roman times, as they had been for centuries before. They are commonly called mneimata (the plural of mnema) in the scholarly literature, and the term is often used in Walters’ notebook of his excavations at Kourion in 1895.

These mneimata are essentially rectangular pits cut in the earth or rock for a small number of interments, similar in many respects to modern Western graves. Earth graves were sometimes lined or covered with stone slabs or tiles, while rock-excavated examples often show refinements such as carefully cut sides or ledges for a covering slab. Despite their simpler form, some of these graves show signs of wealth and are sometimes placed in the same cemetery plots as chamber tombs. Both adults (men and women) and children were interred in surface graves. From this it follows that they were not necessarily the burial places of the poor, or predominantly late in date, as was once commonly argued.

At the same time, changes in burial practices are visible at Kourion over time. The cremation burial in Tomb 113 just mentioned, though never very common, is one sign of a shift away from exclusive use of inhumation. The older Hellenistic and early Roman chamber tombs below the Amathus Gate of the city appear to have been abandoned, after which the area was extensively quarried. From the 4th century AD, single burials were commonly placed in stone cists covered with large slabs in the same area as the older chambers. These graves were connected to the surface by small pipes to allow libations to be offered to the dead after the sealing of the tomb. This practice, as well as the offering of grave goods, apparently continued for a time after the advent of Christianity.