1931 Cyprus revolt

The 1931 Cyprus revolt or October Events (Greek: Οκτωβριανά, Oktovriana) was an anti-colonial revolt that took place in Cyprus, then a British crown colony, between 21 October and early November 1931. The revolt was spearheaded by Greek Cypriot nationalists who advocated the Enosis (Union) of the island with Greece. The defeat of the rebels led to a period of repressive British rule known as “Palmerocracy” (Παλμεροκρατία), that would last until the beginning of World War II.

Background

At the outbreak of the First World War, Cyprus was nominally a part of the Ottoman Empire, while in fact being administered by the British Empire as agreed in the Cyprus Convention of 1878. On 5 November 1914, the Ottomans entered the conflict on the side of the Central Powers, prompting Britain to void the Cyprus Convention and annex the island as the two states were now at war. In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Greece in exchange for the Greek intervention into the World War I on the side of the Triple Entente. The Greek government refused the offer as at the time it was embroiled in a deep internal crisis known as the National Schism. Cyprus had already been described as a bargaining chip for negotiating with the Greeks when it was offered in exchange for the deep water port of Argostoli in 1912.

Following the end of the war Britain received international recognition of its claims to the island at the 1923 Conference of Lausanne. Greece was the only country that could potentially contest the decision, based on the fact that four fifths of its population were ethnically Greek. However at the time Greece faced economic ruin and diplomatic isolation as a result of a disastrous defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), thus Greek envoys made no mention of Cyprus at the conference. Cyprus then attained the status of a crown colony and the number of the Cypriot Legislative Council members was increased in favor of British officials. The aforementioned setbacks did not put a halt to the spread of the Megali Idea (Great Idea) and the closely related Enosis (Union) ideologies, the ultimate goal of which was the incorporation of all areas populated by Greeks into an independent Greek state. The November 1926 appointment of Ronald Storrs (a philhellene) as the new governor of Cyprus, fostered the idea among Greek Cypriot nationalists that British rule would be a stepping stone for the eventual union with Greece.

Their relationship was to sour in 1928, when Greek Cypriots refused to take part in the celebration of the 15th anniversary of the British occupation of Cyprus. Greece once again appealed for calm, limiting the spread of anti-colonial articles in Greek Cypriot newspapers. Education became another arena of conflict with the passage of the Education Act, which sought to curtail Greek influence in the Cypriot school curricula. The Church of Cyprus which at the time played an important role in the social and political life of the island became one of the bastions of Greek nationalism. Cypriot irredentists also lamented the supposedly preferential treatment of Malta and Egypt at the expense of Cyprus. Relations worsened further when the British authorities unilaterally passed a new penal code which permitted among other things the use of torture. In 1929, Legislative Council members Archbishop of Kition Nikodemos and Stavros Stavrinakis arrived in London, presenting a memorandum to the secretary of colonies Lord Passfield which contained demands for Enosis. As with previous such attempts the answer was negative.

Conflict

In September 1931, Storrs blocked a Legislative Council decision to halt tax hikes that were to cover a local budget deficit. Greek Cypriot MPs reacted by resigning from their positions. Furthermore, on 18 October, Archbishop of Kition Nikodemos called Greek Cypriots to engage in acts of civil disobedience until their demands for Enosis were fulfilled. On 21 October, 5,000 Greek Cypriots, mostly students, priests and city notables rallied in the streets of Nicosia while chanting pro–Enosis slogans. The crowd besieged the Government House, following three hours of stone throwing the building was set on fire, the rioters were eventually dispersed by police. At the same time British flags were stripped from public offices across the country, often being substituted with Greek ones. Order was restored by the beginning of November.The British accused the Greek general counsel in Nicosia Alexis Kyrou (a Greek nationalist of Cypriot descent) of instigating the revolt. Kyrou had indeed worked behind the scenes to create a united opposition front against the British prior to the revolt, in direct disobedience to the orders he received from Athens. A total of 7 protesters were killed, 30 were injured, 10 were exiled for life, while 2,606 received various punishments ranging from prison terms to fines on account of seditious activities.

The British obsession of balancing the budget, increasing taxes, and using Order-in-Council measures played an important part in the Greek-Cypriots’ decision to seek a greater say in the political and administration affairs of their country. However, Britain was not prepared to relinquish their hold on power.

The enosists (unionists) saw this as a wonderful opportunity to push their case for union with Greece. Their actions would test British resolve who used force to quell Greek-Cypriot nationalism resulting in Governor Storrs (November 1926- October 1932) dissolving the Legislative Council (LC).

A crowd had gathered outside the Commercial Club in Nicosia on October 21, 1931 to hear the news that members of the LC had resigned over the budget. Speeches made inside the club criticized the injustices of British rule and shouts for enosis with Greece could be heard outside in the street. The crowd increased from a few hundred to a few thousand. A priest “mounted the makeshift platform and declared a revolution was to be underway.” A Greek flag was flung which the priest kissed symbolising the Cypriots demands for enosis with mother Greece. They were continual cries “To Government House, To Government House” where protestors saw this building as a symbol of British rule.

Police learned that a large number of demonstrators was approaching Government House, so additional police was placed at the entrance to stop them from entering the Governor’s residence. The protestors broke through the police line where they shouted enosis and demanded the Governor to come out and hear them. Storrs was prepared to listen to their grievances, so as long as they maintained a ‘respectful distance’ by inviting one or two of their leaders. However the situation turned nasty when some demonstrators started throwing bricks which smashed windows and someone got on top of the roof of Government House unfurling the Greek flag. Storrs issued instructions that force should be used to disperse the crowd.

Additional police reinforcements were brought to stop the stone-throwing demonstrators who had smashed many windows of Government House and even telephone equipment had been destroyed. The Colonial Secretary’s car along with some abandoned police cars had been torched. Unfortunately, the fire spread to Government House, which eventually was engulfed in flames.

The Riot Act was read in English and Greek, ordering the demonstrators to disperse, they refused to listen. Police fired a volley of shots resulting in 7 men being wounded and “two collapsed to the ground.” The rifle volley had caught the crowd by surprise who scattered into the streets of Nicosia. However this did not save Government House. The British Telegraph newspaper ran headlines such as ‘A Capital under Mob Rule’ and ‘Incendiarism by Cyprus Rioters’ to portray the Greek Cypriots in a negative light.

Storrs was worried that this rebellion might spread to other parts of the island. A curfew was proclaimed on October 22 with notices plastered on walls in both Greek and English in Nicosia. However, troubles broke out in Larnaca, Famagusta, Kyrenia, Limassol and Paphos that continued until early November. Storrs took the drastic step of deporting the ringleaders George Hajipavlou, Dionysios Kykkotis, Theofanis Tsangarides, Theofanis Theodotou, Theodoris Kolokassidis, and the two bishops of Kition and Kyrenia to Malta barring them from returning to Cyprus. He believed that such a measure would defuse the political tensions on the island.

To complicate matters, the Greek Consul Alexandros Kyrou left the island accused of being involved in the “anti-British disturbance.” The British revoked his authority (exequatar) as Consul where he would never be allowed to resume his diplomatic post in Cyprus. Kyrou’s involvement would have angered the Greek Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos who saw this as undermining his nations good relations with Britain.

There was a permanent garrison in Cyprus consisting of three officers and 123 men stationed in the Troodos Mountains which was immediately summoned to Nicosia. Storrs telegraphed for additional British troops from Egypt to be dispatched by air and also the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean fleet to send an aircraft carrier. British troop and naval reinforcements from outside began to arrive and slowly established some semblance of law and order on the island. RAF airplanes flew over Cypriot villages to keep a watchful eye on the situation from the air.

At the end of the demonstrations, some 30 people were wounded and six Greeks killed. More than 2,000 rioters were convicted who served sentences of varying periods. A “reparations Impost law levied fines of £34,315 on towns and villages held to be collectively responsible for seditious actions.” The idea of collectively punishing towns and villages for disloyal action was unjust and could only harm the relations between the British and Greek-Cypriots.

Storrs appreciated “the goodwill of the large Muslim population and other minorities towards the Government never wavered throughout the disturbances.” There was no suggestion that the demonstrations had been ‘premeditated’ or ‘prearranged.’ The serious troublemakers were ‘roughs’ and ‘students’ where “respectable citizens either kept out of the way, in order to avoid the stigma of disloyalty, cheered for union.” According to Storrs, the idea of union may not have had the support with some sections of the Greek-Cypriot community who probably prospered under British rule.

The Greek press fully supported the Greek-Cypriots’ action for enosis and criticised the actions of the British troops on the island. In a speech to the Greek parliament on November 18, Eleftherios Venizelos criticized the stance of the Greek press towards the British administration in Cyprus and British Government. Whilst he sympathised with the position of the Greek-Cypriots, he would not allow organisations to use Greek soil for insurrection in Cyprus. It was up to Britain to decide whether to keep Cyprus or not and its responsibility to help the Cypriots realize their aspirations. Venizelos disapproved of the Greek-Cypriot demonstrations of October 1931 and wished to maintain friendly relations with Britain. He continued to display his ambivalence towards the Cyprus question as he did during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

The October riots of 1931 shook the British administration to its core thus forcing Governor Storrs to take strong energetic measures against the rioters and also leading to the dissolution of the LC. This was the first time the Greek-Cypriots challenged British authority , however, the issue of enosis remained alive in the national consciousness of Greek-Cypriots for another two decades when they commenced their war of independence from British rule in April, 1955.

Aftermath

The revolt led to the dismissal of Kyrou whose actions had inadvertently damaged both the Enotic cause and the Anglo–Hellenic relations. The revolt also dealt a blow to Storrs’ career, he was soon transferred to the post of Governor of Northern Rhodesia. The Legislative Council and municipal elections were abolished, the appointment of village authorities and district judges was relegated to the governor of the island. Propagating Enotic ideas and flying foreign flags was banned as was the assembly of more than 5 people. The new measures were aimed at suppressing the operation of the Orthodox church and communist organisations. Censorship had a severe effect on the operation of newspapers especially those associated with left wing politics. Cyprus thus entered a period of autocratic rule known as Palmerokratia (Παλμεροκρατία, “Palmerocracy”), named after governor Richmond Palmer, which started shortly before the revolt and would last until the beginning of World War II. The revolt has been described as the most severe anti-colonial movement that Britain faced in the interwar period. The revolt is known in Cypriot historiography as Oktovriana (October Events).

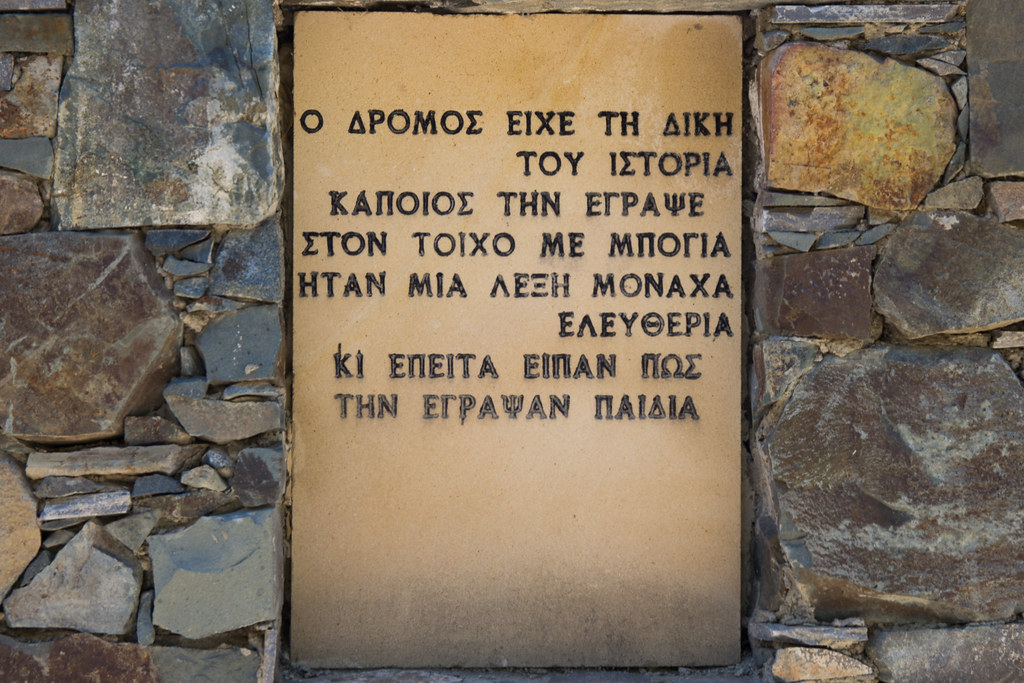

Monuments commemorating the October Events were erected in Strovolos and Pissouri in November 2007 and October 2016 respectively.