Cyprus internment camps were camps run by the British government for internment of Jews who had immigrated or attempted to immigrate to Mandatory Palestine in violation of British policy. There were a total of 12 camps, which operated from August 1946 to January 1949, and in total held 53,510 people.

Great Britain informed the United Nations (UN) on February 14, 1947, that it would no longer administer the Mandate for Palestine. This prompted the UN General Assembly to recommend partition of Palestine into independent Jewish and Arab states on November 29, 1947. Some 28,000 Jews were still interned in the Cyprus camps when the Mandate was dissolved, partition was enacted, and the independent Jewish State of Israel was established at midnight Palestinian time on May 14, 1948. About 11,000 internees remained in the camps as of August 1948, with the British releasing and transporting the internees to Haifa at the rate of 1,500 a month. Israel began the final evacuation of the camps in December 1948 with the last 10,200 Jewish internees in Cyprus mainly men of military age, evacuated to Israel during January 24–February 11, 1949.

History

Anti-deportation protest rally, Tel Aviv, 1946

In the White Paper of 1939, the British government decided that future Jewish immigration to Palestine would be limited to 75,000 over the next five years, with further immigration subject to Arab consent. At the end of World War II, there were still 10,938 immigration certificates remaining but the five years had expired. The British government agreed to continue issuing 1,500 certificates per month, but the influx of Jews, especially from the displaced person camps in Europe, well exceeded that number. It was decided in August 1946 to hold many of the illegal immigrants on Cyprus. Previous places of detention had included Atlit detainee camp in Palestine, and a camp in the Mauritius. A few thousand refugees, mostly Greeks but also a “considerable number” of Jews from the Balkans, had reached Cyprus during the war years.

At its peak there were nine camps in Cyprus, located at two sites about 50 km apart. They were Caraolos, north of Famagusta, and Dekhelia, outside of Larnaca. The first camp, at Caraolos, had been used from 1916 to 1923 for Turkish prisoners of war.

Some 400 Jews died in the camps, and were buried in Margoa cemetery.

Background

The majority of Cyprus detainees were intercepted before reaching Palestine, usually by boat. Some were on vessels that had successfully run the British blockade, but were caught in Palestine. Most of them were Holocaust survivors, about 60% from the displaced person camps and others from the Balkans and other Eastern European countries. A very small group of Moroccan Jews was also in the camps. The prisoners were mostly young, 80% between 13 and 35, and included over 6,000 orphan children. About 2,000 children were born in the camps. The births took place in the Jewish wing of the British Military Hospital in Nicosia. Some 400 Jews died in the camps, and were buried in Margoa cemetery.

Transshipment and detention camps on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, in which the British authorities held Jewish “illegal” immigrants, most of them European survivors of the Holocaust trying to enter Palestine. On August 7, 1946, the British government made a decision to detain these Jews in Cyprus, hoping that this deterrent would put an end to Jewish immigration. The decision was geared to the British policy of breaking the power of the “Hebrew resistance movement” in Palestine. But before long the British came to realize that detention was not achieving the desired aim. The would-be immigrants continued their attempts to reach Palestine despite violent clashes with British troops and transshipment to Cyprus. By December 1946 the British government, under pressure from the Jewish Agency and in view of the rapid rise in the number of people interned in the Cyprus camps, was allotting half the legal immigration quota (that is, 750 visas, or certificates, a month) to the Cyprus detainees.

The British were successful in apprehending most of the 70,000 illegal immigrants who embarked for Palestine. Nonetheless, as space for refugees on Cyprus became scarce and ships continued to sail from Europe carrying ma’apilim, it became apparent to the British that the policy of detention in Cyprus was not successful in deterring the Ha’apala movement.

The use of the Cyprus detention camps began on August 13, 1946, and ended on February 10, 1949, when the last group of detainees left for what had become the state of Israel. During this period, fifty-two thousand Jews passed through the Cyprus camps, having been taken off thirty-nine boats in their attempts to get to Palestine. Twenty-two hundred children who were born in the camps must be added to this number. Some of the detainees spent only a few months in Cyprus, but many were held there for a year and longer. Responsibility for setting up the camps and for their administration and security was of the British army in Cyprus, which handled the camps according to the rules applicable to prisoner-of-war camps. There were two kinds of camps. The “summer camps,” of which there were five, were located at Kraolos, near Famagusta, and the detainees in them were housed in tents. The seven “winter camps” were located at Dekalia, north of Larnaca. Here the housing consisted of tin huts and some tents. Conditions in the camps were quite harsh, especially for mothers of children and babies.

Living Conditions

The tents and barracks were overcrowded. There was no privacy, and families had to share accommodations with single persons. There were no partitions, no lighting fixtures, and no furniture except beds. The food supplied by the British army was of poor quality. Because of the inadequate facilities in the field kitchens, food was wasted and people went hungry. The detainees also suffered from a lack of clothing and shoes, which the British supplied only in limited quantities from army surplus. The insufficient supply of water, particularly in the hot summer months, caused sanitary conditions to deteriorate and led to skin diseases and infections. Most of the British officers and troops in charge of the camps carried out their duties indifferently or unwillingly. Those who wanted to ease the refugees’ lot for humanitarian reasons had little authority or resources.

The British administration in Palestine, which was charged with establishing and maintaining the camps, had to bear the costs out of its budget, which in any case showed a deficit, and it sought to put the responsibility for the welfare of the detainees on the Jewish Agency and the Joint Distribution Committee (also known as the Joint). This put the Jewish Agency in a dilemma. It did not recognise the legality of the detention, nor did it want to relieve the British authorities of their responsibility for the maintenance of the camps and the detainees’ state of health. The Agency therefore asked the Joint Distribution Committee to take on responsibility for the welfare of the camp population, which the Joint readily did. As early as September 1946, a few weeks after the camps were set up, the Joint was already engaged in welfare operations there, which they maintained throughout the camps’ existence.

The majority of the youngsters were put into one camp, Camp 65, which became a kind of youth village.

The Joint greatly reduced the hardships from which the refugees suffered. It recruited medical and welfare teams in Palestine to run nurseries and clinics in the camps, it improved the quality of food rations for those in special need and supplemented the basic food supplies of the general camp population, it catered to religious requirements, and it set up a bureau for the search of missing relatives. The provision of educational facilities for the children and teenagers (of whom there were large numbers in the camps, most having been orphaned in the Holocaust) was yet another task taken on by the Joint, in partnership with Youth Aliya. The majority of the youngsters were put into one camp, Camp 65, which became a kind of youth village. There, Youth Aliya educational teams established a school system based on the few teachers found among the refugees.

The welfare teams recruited in Palestine included Jewish Agency appointed emissaries of various political movements. Morris Laub, the Joint’s director in Cyprus, became the spokesman and representative of the detainees vis-א-vis the British authorities on the island. The detainees in the Cyprus camps were relatively young, with 80 percent of them between the ages of thirteen and thirty-five. Thus, they were among the more spirited and lively survivors of the Holocaust. They came to the camps as members of youth movements, immigration groups, and political parties imbued with a strong Zionist ideology. Their ideology and self-discipline enabled them to adapt to the conditions in the camps. In addition to being deprived of their liberty and exposed to harsh physical conditions, the detainees also suffered greatly from the enforced idleness of the camps. Efforts to keep them busy with cultural activities met with difficulties, owing to lack of means and scarcity of qualified personnel.

An important contribution was made by emissaries from Palestine who lived with the refugees in the camps. Some of these were “legal”: representatives of the various Zionist movements, welfare workers under Joint auspices, and teachers dispatched to Cyprus by the Rutenberg Teachers’ Seminary. Others were “illegal”: they were sent to Cyprus by the Palmah, the underground strike force of the Hagana (the Yishuv’s underground military organization), to provide the young people in the camps with military training and prepare them for service with the Hagana when they arrived in Palestine. Living among the detainees and sharing their lot, these emissaries had great influence. They represented the Jewish national institutions and were the link between the refugees and the Jewish population in Palestine.

A few of the refugees who had second thoughts applied to the British authorities to return to the country from which they had set out. But generally, despite all their suffering, the Cyprus detainees displayed impressive moral strength and staying power during their internment. Though there were no written laws and no real sanctions that could have been applied, not a single criminal act was recorded among the detainees.

Escape attempts

A number of escape attempts took place while the camps were active. The most significant was in August 1948, when an estimated 100 inmates escaped a detention camp via a secret tunnel the British believed had been dug over a period of six months. The British believed that the escapees were being met by Jewish representatives in Cyprus, and “selected male specialists” among the refugees were being put on small boats capable of reaching Israel in 24 hours, which were being brought to Cyprus at night. Some 29 refugees were arrested over the incident and given prison sentences ranging from four to nine months. One man managed to escape while being transported from court to prison. In January 1949, as the British began deporting the final batch of inmates to Israel, an unspecified number of Jews who had escaped the camps and had remained at large in Cyprus turned themselves in so they could be sent to Israel. In February 1949, the evacuation of the camps officially ended, although some families and individuals remained in Cyprus until November 1949 due to health reasons or because they had young babies.

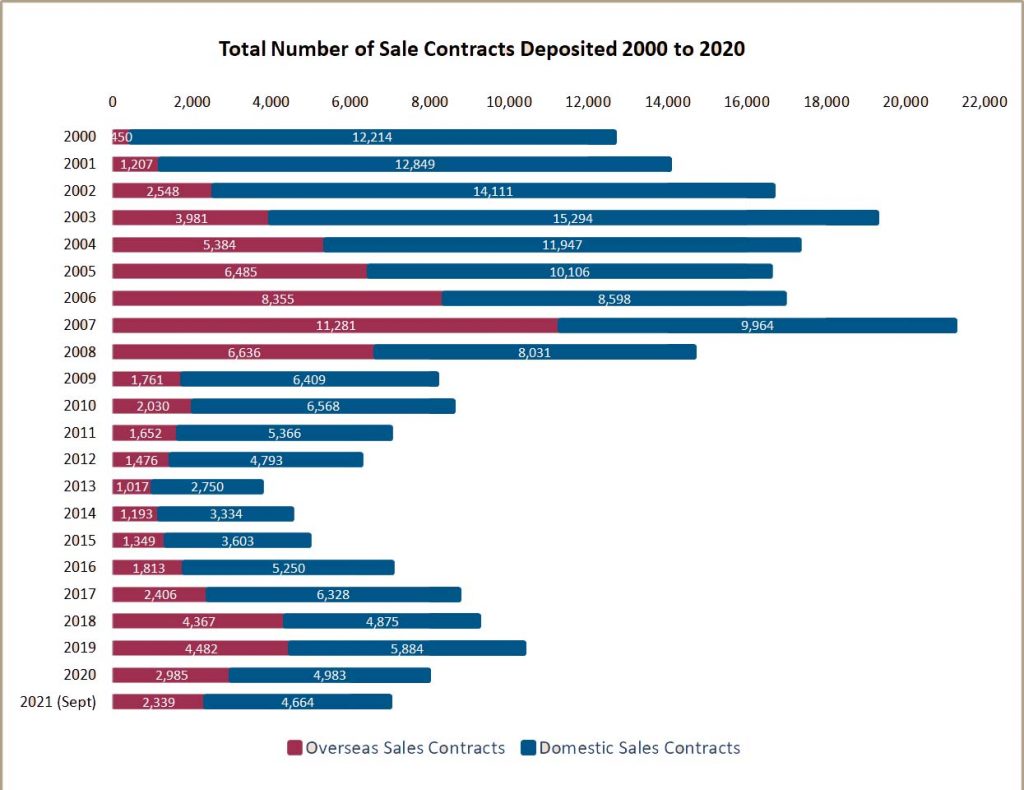

Immigration quota system

From November 1946 to the time of the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948, Cyprus detainees were allowed into Palestine at a rate of 750 people per month. During 1947-48, special quotas were given to pregnant women, nursing mothers, and the elderly. Released Cyprus detainees amounted to 67% of all immigrants to Palestine during that period. Following Israeli independence, the British began deporting detainees to Israel at a rate of 1,500 per month. They amounted to 40% of all immigration to Israel during the war months of May–September 1948. The British kept about 11,000 detainees, mainly men of military age, imprisoned throughout most of the war. On January 24, 1949, the British began sending these detainees to Israel, with the last of them departing for Israel on February 11, 1949.