Roman Cyprus

Cypriot History

OVERVIEW

The Imperium Romannum differed fundamentally from Alexanders [the Great] empire in its social system, in its government, and as a geopolitical structure. The main territory and the centre of the power now lay in the west, while the control over part of the Near East (which Seleucid empire had already been unable to hold) was lost forever. Iran, Mesopotamia, and Arabia stayed outside the Roman Empire; from the first century onwards, they provided the setting for the Arsacid Parthian Empire, the new great power in in the East and Romes chief opponent, whose political successors were to include the Sassanids and, in the course of time, Islam. The “eastern question”, seemingly resolved through Hellenism, once more came to the fore.

Roman Cyprus was a minor senatorial province within the Roman Empire. While it was a small province, it possessed several well known religious sanctuaries and figured prominently in Eastern Mediterranean trade, particularly the production and trade of Cypriot copper. As it was situated at a strategically important position along Eastern Mediterranean trade routes, Cyprus was controlled by imperial powers throughout the first millennium B.C. including: the Assyrians, Egyptians, Macedonians, and in particular the Romans. Cyprus was annexed by the Romans in 58 B.C., but until 22 B.C. when Cyprus became an official senatorial province, control over the island fluctuated between the Romans and the Ptolemaic Empire. From the Battle of Actium in 31 BC until the 7th century Cyprus was controlled by the Romans. Cyprus officially became part of the Eastern Roman Empire in 293 AD.

Under Roman rule, Cyprus was divided into four main districts, Salamis, Pafos, Amathous, and Lapethos. Pafos was the capital of the island throughout the Roman period until Salamis was re-founded as Constantia in 346 AD. The geographer Ptolemy recorded the following Roman cities: Pafos, Salamis, Amathous, Lapethos, Kition, Kourion, Arsinoe, Kyrenia, Chytri, Karpasia, Soli, and Tamassos, as well as some smaller cities scattered throughout the island.

Information about Cyprus during Roman rule is based primarily on archaeological findings and epigraphy. There is sparse literary evidence and very infrequent texts on which to base our knowledge

With the new border between East and West running along the edge of the Syrian desert and through the mountains of Armenia, Cyprus again changed its historic position. During the Hellenistic period, After Alexander had abolished the threshold between Europe and Asia, it was a secondary border zone between Egypt and Seleucid Syria. Now it was placed closer to the centre, amidst the political calm of Pax Romana.

However, almost twenty years of turmoil under the declining republic had to pass before Cyprus could enjoy the quiet and uneventful existence of a minor Roman province. Rome had annexed the island in 58 B.C. under a double pretext. The disputed will of the last legitimate Ptolemaic ruler had promised Egypt -and thereby Cyprus- to Rome; at the same time, Cyprus, as a base of piracy in the eastern Mediterranean, was to lose its autonomy altogether. But the real reasons behind this scheme were political and economic. After the annexation of Syria, Cyprus as the only independent Hellenistic monarchy, represented the last stage in the encirclement of Egypt; its wealth and its natural resources further made it almost irresistibly attractive to a government and an aristocracy permanently in financial straits. Another important point had to be considered; by `entrusting’ M. Porcius Cato with the official takeover of the island, Clodius Pulcher, one of Caesars chief followers, had succeeded in removing from Rome a difficult contender at a critical time.

The fate of the island, for the time being incorporated in the province of Cilicia, illustrated the part played by straightforward greed and financial speculation in the Roman takeover. Like other provincial territories in the late republic, Cyprus provided many an opportunity to make or at least recover fortunes. Ptolemaios, whom Cato offered the position of High Priest of Aphrodite in place of his former throne, had committed suicide by poison, and Cato administered the former royal fortune, which had yielded a revenue of 7,000 talents per year, with the utmost integrity. Cicero, who was governor of Cyprus 51-50 B.C., though ostensibly correct, proved himself in the end unable to resist some unsavoury financial machinations. Otherwise, the island was ruthlessly exploited by officials and businessmen for the next ten years. The terms of a `loan’ given to the city of Salamis by a consortium headed by M. Brutus were highly revealing; the interest fixed at 48%, was collected by Roman cavalry.

During the Roman civil war, Cyprus resumed a brief romantic role under the Egyptian crown, when it was returned to Cleopatra, first by Caesar (47 B.C.) after the end of the Alexandrine war, and again by Marcus Antonius (36 B.C.). Octavians victory at Actium (31 B.C.) finally brought the island under Roman rule, under which it was to remain for nearly three centuries.

In the Roman inland lake, which the Mediterranean had become, Cyprus had little strategic significance. In 22 B.C. after the general consolidation in the east, Cyprus exchanged its status from an [imperial]- i.e. under the direct administration of Augustus (Octavian) and under military occupation- to a [senatorial] province. Separated from Cilicia in 27 B.C., Cyprus was ruled by a pro-consul as civil governor. Its capital was still Paphos, -Augusta Claudia Flavia Paphos-, which had steadily grown in importance since the Ptolemies as a political and religious centre and, as a result of the silting-up of the harbour of Salamis, one of the major ports. Paphos, Amathus, Salamis, and Lapethos each formed and administrative region. With municipal autonomy, elected officials and a considerable degree of independence in religious and cultural matters, the island enjoyed greater freedom than under Egyptian rule. The -Koinon- of the different cities, which was still chiefly an institution for the advance of the cult of the Emperor and for the organization of games, like the Roman senate, had the right to issue bronze coinage.

To Cyprus, the centuries of the Pax Romana formed an uneventful, though contended period. a population unused to political independence or democratic institutions did not find Roman rule oppressive. The political peace of the island suffered a single interruption through the great Jewish rising of A.D. 115-6 which affected Cyprus as it did Cyrenaica and Egypt; the excesses of the rebels -vastly exaggerated contemporary figures speak of 240,000 dead on Cyprus alone- were followed by terrible counter measures under Trajans general Lusius Quietus and by the expulsion of the Jews from the island.

In other spheres, after a brief depression in the first century B.C. Hellenism continued to flower under a competent and liberal Roman administration. The early years of the Roman empire brought outstanding prosperity to Cyprus; the luxury of its cities, as well as the reputation for immorality and indolence -[infamem nimic calore Cypron]- inevitably bring to mind the years of Lusignan rule, except that, in contrast to the Middle Ages, it was thriving in the centre of a peaceful political system and enjoying all the advantages of a great self-sufficient economic region with a unified legal and financial system. The old-established trade of India and Southern Arabia with Italy and the west, in which Cyprus had long established a secure place, intensified; the island itself was opened up by a system of Roman roads and the ports were further developed. Its diverse produce -timber, wine, oil, grain, copper, and silver- found a ready market throughout the imperium; it was a Cypriot boast of this period, that it was possible to build and equip a ship entirely with local materials.

All the important centres were transformed by the town-planners, even more than in Hellenistic times. Great -Fora-, colonnaded squares, temples, theatres, thermae, and aquaducts were built, above all in Paphos and Salamis; Soli acquired its first theatre and a public library, Curium extended the sanctuary of Apollo Hylates. In Cyprus, as elsewhere, every aspect of day-to-day existence as well as the cultural and intellectual life was deeply influenced by the Mediterranean, Hellenistic-inspired, civilisation of Imperium Romanum. The process of the assimilation and Romanization /Hellenization of the people of the island, begun in the fourth century B.C., was completed, although as in other eastern provinces, the oriental tradition lay below the Hellenistic veneer. Thus the cult of Aphrodite, whose origins in the rites of the eastern goddess of fertility had never been forgotten, continued; her temple in old Paphos has remained one of the most famous shrines of the Mediterranean until the present day. Roman coins displaying the temple temple with the conical stone (which takes place of the cult image or fertility symbol) carried the fame of the goddess throughout the whole empire; emperors like Titus and Septimius Severius brought offerings to her. A road flanked by small chapels led from New Paphos to a much frequented pilgrimage centre; `Men and women from many cities annually march in procession to Paphos along this road’.

Yet, in the course of time, the cult of Aphrodite gave way to Christianity, leading eventually to the replacement of the goddess by the Panagia. Its geographic position, as well as its strong Jewish population -composed to some extent of refugees from various persecutions- helped to make Cyprus one of the earliest missionary realms. Although St Paul and St Barnabas (Joseph, the Levite, from Salamis) met with little success amongst the Jews of Cyprus during their mission of the year A.D. 45, St Paul was able to convert the Roman Pro Consul Sergius in Paphos; the island thus became the first territory to be ruled by a Christian, even though only for a short span. On a second missionary journey the hostility of the Synagogues proved Barnabas undoing and he suffered martyrdom in his native city. The rise of the Cypriot church between these events and the reign of Constantine the Great is shrouded in legend; its first genuinely historic representatives -St Hilarion, St Epiphanios of Salamis, and St Spyridon of Tremithus- are contemporary with the Council of Nicaea (325). At least three bishoprics, Paphos, Salamis, and Tremithus, were established at that time. The expansion of Christianity therefore cannot have been altogether negligible, although the temples of Paphos and Soli, amongst others, were still in use in the fourth century A.D. While we know practically nothing of the relationship with pagan cults and their centres on the island, it is clear that the synthesis of old and new cultures- by no means confined to Cyprus even then- had already begun, as the church of Panagia Aphroditissa, which was built slightly later at Paphos, proves. The most remarkable evidence of the meeting of old and new faith is the early fifth century A.D. mosaic inscription at Curium, where Christ is described in archaistic couplets as the protector of the city in place of Phoebus Apollo.

The turmoils of the third century, the military anarchy of the soldier emperors and the wars on the northern and eastern frontiers of the empire obviously barely touched the island except, briefly, in A.D. 269, when a Gothic fleet reached Cyprus in the course of its Mediterranean travels in search of pillage, having previously attacked Crete and Rhodes. The economic depression, similarly, is less marked than in the west of the empire, although the trade with the east suffered noticeably under the pressure of the new Persian dynasty of the Sassanids, who had come to power in A.D. 224. Only the struggles within the Empire under Diocletian and Constantine (A.D. 284-337) ended the peaceful isolation of Cyprus. Once more, the island was cast into the stream of events and its destiny took a new turn.

POLITICAL TIMELINE

Cyprus had been under the rule of Ptolemaic Egypt prior to it becoming a Roman province. King Ptolemy, son of the King of Egypt Ptolemy IX Lathyros, reigned over Cyprus from 88 to 58 BC. After Ptolemy refused to put up ransom when Publius Clodius Pulcher was kidnapped by Cilician pirate, Cyprus was abruptly annexed by Rome and added as part of the Cilician province. The Lex Clodia de Cyprus was passed by the Concilium Plebis in 58 BC and Cato was sent to Cyprus as its new proconsul. Cato offered Ptolemy the position of the High Priest at Pafos but Ptolemy refused and instead took his own life. Cato sold much of the royal possessions and brought back 7000 talents to Rome after taking his share of the profits.

During this time Cyprus was exploited by the Roman rulers who saw positions in the provinces as stepping stone in Roman politics. In 50 BC Cicero Minor, son of the famous orator, was given the proconsulship in Cyprus and was more sympathetic to the Cypriot people. However, by the end of his proconsulship there was much political turmoil in Rome and Rome lost control of Cyprus in 47 BC. Marc Antony and Octavian, later Augustus, were struggling for power after Julius Caesar’s death and in 40 BC Marc Antony gave Cyprus to Cleopatra VII, Queen of Ptolemaic Egypt, as a gift. The Battle of Actium in 31 BC marked the end of the civil war with Octavian gaining control of all of Egypt and Cyprus. Cyprus was left under control of Octavian’s legate until it could be further dealt with. In 22 BC Cyprus was separated from the Cilicia and became a senatorial province without a standing army.

Cyprus was divided into four regions with thirteen known cities with Nea Pafos becoming the capital.[7] Cyprus was allowed a large amount of autonomy remaining mainly Greek in culture while adopting and adapting Roman customs. No Roman colonies were settled on the island. During this time period there are very few primary literary sources that mention Cyprus, let alone provide a detailed history. However, epigraphic and archaeological evidence indicates thriving economic, culture and civic life in Cyprus throughout the Roman period.

In 45 AD Saint Paul and Saint Barnabas visited Cyprus as part of Paul’s first missionary journey to convert the people to Christianity.[8] St. Barnabas returned for a second visit in 49 AD but the spread of Christianity was slow, especially in the rural areas. After the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD by Vespasian, the Roman Emperor, and his son Titus there was a large influx of Jewish refugees into Cyprus. In 115-117 AD a widespread Jewish revolt (Kitos War) resulted in thousands of deaths in Cyprus and around the Eastern Empire and in the expulsion of Jews from Cyprus. In 269 AD there was a brief Gothic invasion (Battle of Naissus) throughout the eastern empire including Cyprus. In 293 AD Cyprus became part of the Eastern Empire as the Roman Empire was divided under the Diocletianic reforms.

ROMAN MILITARY ON CYPRUS

There was very little significant Roman military presence on Cyprus, with the exception of two notable incidents; a local council was barricaded into their own council house by an equestrian troop and the Jewish massacre at Salamis which required outside military intervention. The proconsul had a legatus subordinate, which points to at least a token military presence, but there is almost no evidence of there being anything larger than the praetorian bodyguards on the island.

Every province of the Roman Empire was required to send men to fill the ranks of the Roman army as conscripts and Cyprus was no exception. The Cypriots contributed some 2000 men to the foreign auxilia at any one time, but there are no notable military figures from Cyprus. There are two cohorts of auxiliary troops that performed well enough to be given the honor of citizenship before their 25 years of service was up, but other than those there is no other known outstanding Cypriot units.

ROMAN ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEM

The Roman administrative system was also fairly light; it seems that only unfavored citizens were sent to govern the island. The basic structure consisted of a proconsul at the top representing the Roman Senate and the emperor with two assistants in the form of a legatus and a quaestor. The proconsul had several duties, including:

High court judicial duties; if the magistrate and the local council couldn’t rule on it, it was brought to the proconsul investing the high priest (of the Imperial cult) with his power as the representative for the emperor consecrating Imperial statues and buildings in the name of the emperor he promoted public and civic (construction) works such as aqueducts, roads, and centres of entertainment (such as theatres) it was his responsibility to decide on funding for “extravagant projects” such as honorary equestrian statues or repaving sanctuaries he was also responsible for the internal security of the island

The Cypriots were essentially peaceful; there is no mention of outlaws needing to be dealt with or crimes severe enough to need police intervention, there was no real policing force on the island for the proconsul to oversee. The closest thing to a police force was a hipparch in office in Soli under Hadrian’s rule, but this seems to have been a temporary situation.

Under the proconsul and the legate were the local councils; these were led by archons who were elected annually from among the members of the council. There were several other positions associated with the councils, but they are all local officials and not directly part of the Roman administrative structure.

The quaestor handled tax collection on the island; he had a board of ten Cypriots in each city to help him with his duties. In addition to this force, there were publicani who would bid for the right to collect taxes in each region. The terms of office for the proconsul and the legate were staggered with that of the quaestor, that is to say the proconsul and the legate would see the last six months of the old quaestor’s term and the first six months of the new one’s term.

ECONOMY AND TRADE

ECONOMY

The Roman period was one of the most prosperous in Cyprus’ history. Evidence of luxury items acquired through trade, impressively large administrative buildings in cities like Salamis, and richly decorated mansion homes like those found in Pafos point to a thriving economy. The island was mostly self-sufficient and prospered through the utilization and trade of natural resources. After the Romans annexed Cyprus in 58 B.C., it entered into a period of production and widespread trade facilitated by the pax romana. This is shown in the archaeological evidence of the coastal cities flourishing, Cypriot markets in Syria and Palestine, and extensive coin circulation.

The City was the basic economic unit of the Roman Empire; it could interact with its surrounding agricultural hinterland in one of two ways. In the first, a sort of symbiotic relationship, the city would act as a redistribution center and manufactured goods needed by the agricultural area supporting it. In the second, a more parasitic relationship, the city center would redistribute agricultural surplus while manufacturing goods to be sold or traded with other centers. The role of the city was determined by its proximity to an important trade route. The major coastal cities of Cyprus which showed this kind of economic growth were Pafos, Amathous, and Salamis.

The Roman emphasis on the importance of cities was indicated by its dedication to constructing a network of roads. In Cyprus, roads were initially funded by the Emperor, but the island soon grew rich enough to finance its own construction in the period of Severan dynasty.

The great wealth of Cyprus came from its vast system of trade. Cypriot trade economy was based on resources of the island: wine, oil, grain, copper, minerals, timber, glass, and shipbuilding. With the port cities acting as distribution centers, Cyprus had connections with other locations across the Mediterranean, and seafaring was an important aspect of Cypriot daily life and culture. The extent of trade can be proven archaeologically through the wide array of foreign items found on the island, particularly coins.

Despite the destruction caused by six earthquakes that wracked the island in the Roman period, the Cypriot economy remained relatively steady. The role of the port cities in trade were crucial to the Roman administration; after an earthquake in AD 76 destroyed the city of Kourion, Imperial Rome sent immense amounts of funding to rebuild the city, as evidenced by a large influx of coins in the following year.

ROADS

Ancient roads can be studied through literary, epigraphic (e.g. milestones), topographical, and archaeological evidence. The division of Cyprus into two, the buffer zone and military occupied areas make many parts of the island unavailable for study. It is estimated that 10% of the island is inaccessible for various reasons.[12] Studying the Roman road system and its milestones helps in partially establishing the boundaries of territories in Cyprus.

There are several sources that can be used to get information about Cyprus’ ancient roads. The Geography of Strabo (23 AD) gives several distances and mentions the highway between Palaipafos and Neo Pafos. Pliny the Elder, in Natural History (77-79 AD) talks about the size of Cyprus and lists fifteen cities, including three no longer extant.

The Peutinger Table (Tabula Peutingeriana) is a 13th-century AD copy of an older map of Roman Cyprus. The exact date of the original Peutinger Table is unknown, but is estimated to be from the 2nd to 4th century BC. It is an illustrated version of an itinerary, which is a list of notable places with descriptions and the distances between each place. The map is distorted, north-south is compressed and east-west is stretched out. The roads on Cyprus are shown as an oval which is bisected by a diagonal section of the road. No other roads are depicted.

The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy also talks about Cyprus but the accuracy of this information varies for different areas of Cyprus. For example, some distances are overestimated, underestimated, or come very close to reality. Ptolemy doesn’t mention any roads. Another map is the Kitchener map (1885). It is useful because it helps to distinguish older roads from the twentieth century roads.

There are also travellers’ reports and local informants. Claude D. Cobham compiled travellers’ reports and descriptions in Excepta Cypria (1918). There are also the works of Luigi de Palma Cesnola and D.G. Hogarth, both of whom used local informants. Their works are useful because it has information about Cyprus during its late Ottoman stage, before the British changed anything.

Milestones are an important source because they give route information and they can be dated. Thirty Roman milestones have been found and recorded. Most of them were in mountainous regions and all are located in the coastal highway circling the island. In other areas of the island, where building materials were scarce, milestones were reused. Milestone inscriptions included the mileage and the names and titles of the rulers that contributed to the milestone placement. From these inscriptions other types of information can be inferred. For example, we know that the major road along the southern coast was a part of the Imperial network. Mitford uses the inscriptions to describe the Emperors’ and other government involvement in the roads. He says that three phases of the Roman Cyprus road network emerges from the inscriptions. First, Augustus and Titus are the self-proclaimed creators of the road system. Second, in the Severan period the responsibility of road repairs was given to cities while the proconsul coordinated their activities. The third phase was a century and a half of stagnation and milestones were reused for Imperial propaganda or to express loyalty.

In the Roman Empire, roads were open for everyone to travel. People traveled on foot, by two and four-wheeled vehicles, or by horse and donkey. In the ancient world, where very few people had maps, roads offered predictability and a guarantee that there were no natural obstacles ahead, which usually meant long detours. Traveling on a road also meant greater speed and the possibility of encountering inns, shrines, and springs.

Before the Roman period Cyprus already had a system of main roads and during Roman rule secondary roads were added. The roads in Cyprus often did not meet Roman standards and preexisting roads were not changed to meet them. Although, milestone inscriptions indicate renovations in AD 198, at least in West Cyprus. During the Severan period road maintenance was a civic duty. Throughout the Roman period it is uncertain if the central government paid for the roads completely or shared the costs with nearby cities.

Informal cross-country roads were used in addition to the formal roads. The roads converged on the main economic center, Salamis. Along with the main roads, minor roads radiated from a city. This layout shows the influence of economic forces in creating roads. These minor roads connected the surrounding areas to the urban market. There were also the benefits of ensuring the import of food into cities, thus reducing the risk of famine.

COINAGE

Although the minting and circulation of Cypriot coins has not yet been exhaustively studied, there is sufficient evidence to show widespread trade routes and interaction with other cultures in the Roman world. There are two main types of evidence in coinage: coins minted in or for Cyprus, and all coins circulating within the province during Roman times. After 30 B.C. the nature of coinage became more “Romanized”; coin type and manufacture did not remain static over time, and styles and imagery of coins changed frequently. Provincial coins were minted at Pafos and Salamis, as well as “regal” coins specific to each reigning Emperor in his time. The Koinon was responsible for the coinage, as well as the emperor cult and organization of festivals. For a detailed compilation of each type of coin for each Emperor during this period.

COPPER

Copper mining in Cyprus has an extensive history which flourished in the Bronze Age and continued into the Roman Period. The extent of copper mining in the Roman Period was scaled down significantly, and were under direct imperial control. The three important cities that continued copper mining in the classical period were Amathous, Tamassos, and Soli. The well-preserved mining site located near Soli was Skouriotissa, which contains chaclopyrite deposits that were extensively mined during Roman Period.[18] Recent analysis and location of slag heaps from Roman mines suggests a shift in the social organization of mining in classical times. Some slag heaps were located almost 2 miles away from the mining location[17] suggesting that the copper workers transported the copper ore away from the mines before they decided to smelt the copper out and work with it. This is a significant change from earlier mining settlements in which the copper was melted on site or very near the place where it was extracted.

RELIGION AND SOCIAL HISTORY

KOINON

In order to maintain some degree of autonomy after control of the island shifted to the Roman Empire, the various cities of Cyprus maintained a collective administrative body that reflected Hellenistic values introduced by the Ptolemaic dynasty at the end of the 4th century. Under the Ptolemies, the cities of Cyprus were allowed a degree of autonomy that was unfamiliar and somewhat unexpected. In order to maintain solidarity throughout the kingdom, the cities formed parliamentary committees with each other. Though the resulting confederation of Cypriot cities does not have an exact date of origin, the term Koinon—meaning “common”—began to appear on inscriptions around the middle of the 2nd century B.C. Little is known about the exact function of the Koinon, though it seems to have been grounded in religion due to its initial associations with religious festivals at the Temple of Aphrodite, which was located at Palaipafos.

The large number of people that gathered at the Temple likely realized a need for religious unity amongst all of them; thus, the Koinon was formed to coordinate pancyprian religious festivals. Soon, the meetings of the Koinon began to stray from strictly religious matters and focus more on the social and political aspects of the country, including unifying the various districts and cities in terms of political representation. These assumptions are based on inscriptions on statues and other dedicatory epigraphical evidence around the island that implies that the Koinon had a presence all over Cyprus, as well as the money and influence to affect many different cities. Thus, the purpose of the Koinon shifted from autonomous parliamentary committees during the Hellenistic period to a religiously motivated pancyprian political body. The administrative privileges of the Koinon, by the end of the Roman period, included minting its own coins, participating in political relations with Rome, and bestowing honorary distinctions upon notable individuals. Inscriptions on statues, as previously mentioned, attest to this final function and indicate the fact that the Koinon was most likely a funded organization which received its dues in the form of an annual contribution from each city.

The Koinon therefore maintained a great deal of power because it essentially controlled all forms of religion on the entirety of Cyprus. This power is later utilized to deify some of the Roman emperors starting with Augustus and ending with the dynasty of Septimius Severus. Known evidence in the form of inscriptions and dedications indicates with certainty that the emperors Augustus, Caracalla, Titus, Tiberius, Trajan, Vespasian, Claudius, Nero, and Septimius Severus and his succeeding dynasty all formed imperial cults that were represented on Cyprus. These cults were mostly formed by the emperors in an attempt to solidify their right to rule and gain religious support as peers of the Roman pantheon of gods.

RELIGION AND IMPERIAL CULTS

As far back in Cyprus’ history as archaeological evidence exists, so too do examples of religion. Around the middle of the 4th century B.C., a new ruling dynasty—the Ptolemies—gained power over Cyprus and established imperial cult over the existing religions on the island. This imperial cult put the king at the head of religious observance on the island, and dictated that he was on an equal footing with other gods. To the average citizen, the king was considered a direct representative or descendant of the gods. It is easy to see the extent to which politics and religion became intertwined not only with each other, but with society as well; the king maintained control over the Koinon, an administrative body founded by the various cities scattered across Cyprus for the purpose of coordinating religious activities and festivals. Imperial cult continued to exist throughout Roman occupation of Cyprus, and a number of unique cults emerged from this transition to the Roman period.

After Augustus gained control of Rome—and Cyprus with it—the island’s inhabitants seemed perfectly willing to accept the divinity of the new emperor. Much of our information about Roman religion on the island comes from five sources: ancient literature, Cypriot numismatics, excavations and archaeological work, epigraphy, and burials. Through an analysis of these sources, where appropriate, scholars have been able to come up with an idea of how Roman involvement affected Cypriot religion.

One example of epigraphy that illustrates the Roman Imperial cult is found on a white marble slab that originated from the Temple of Aphrodite at Palaipafos. Essentially, this text contains an oath of obedience that the priests at the temple would be forced to abide by. The oath invokes the names of the Roman gods in a manner that suggests that the ruler—in this case, the emperor Tiberius Augustus—is comparable or equal to the pantheon of other gods. Each god and goddess named represents a different region of Cyprus; thus, the tablet is basically confirming the entire island’s allegiance to the Roman empire. The tablet leaves little doubt that future generations must continue to support the emperor and his family in all regards. Evidence of imperial cult through inscriptions can be found as far back as the earliest Ptolemaic rulers, and continue on until 391 A.D., when the Roman emperor Theodosius I outlawed all pagan worship in the empire.

The pagan Temple of Aphrodite at Palaipafos retained its religious importance to the island even after the founding of Pafos at the dawn of the Hellenistic period. Ancient literary sources tell us that men and women from all over the island would walk from Pafos to Palaipafos as part of a religious ceremony honoring Aphrodite. It seems that the importance of this religious festival helped maintain the status of the city throughout the Roman period.

The importance of the cult of Aphrodite is unquestionable, along with its wealth. For this reason, the high priest at Paphos was granted far more power than his involvement in mere religious functions; instead, the priesthood became more like a theocracy. Evidence from inscriptions suggests that the high priest may have had a hand in all religious matters across the entirety of the island.

The temple at Palaipafos was the leading center for the emperor cult. At the beginning of the 3rd century A.D., a statue of the Roman emperor Caracalla was consecrated at Pafos. In the year proceeding, a second statue of the emperor was erected, this time at Palaipafos. Inscriptions at the old city suggest that aside from Aphrodite, only the Roman emperor was worshiped there. Even at the new city, worship was reserved to only a few gods and the emperor. These gods were most likely Zeus Polieus, Aphrodite, and Hera, while the emperor was worshiped down to the end of the Severan Dynasty–Septimius Severus—the final emperor who enforced imperial cult. Beginning with Augustus in the early first century, Pafos welcomed the emperor as a living god, and inscriptions prove the promised fidelity of the inhabitants of not only Pafos, but all of Cyprus to the new emperor.

Despite seeming reluctant to acquire the title, Augustus, the first Roman emperor, was treated as a god on Cyprus. Even the emperor’s daughter, Julia, and his wife, Livia, became “the Goddess Augusta and the Goddess the New Aphrodite,” respectively. It seems that there was no shortage of priests and other religious figures more than willing to acknowledge the emperor’s divinity in exchange for recognition from Rome. Titles began to be conferred between Rome and the priesthood to solidify each other’s right to authority. As previously mentioned, the main method by which the imperial cult ordained its members was through an oath of allegiance to the emperor. Countless statues and other monuments were erected in nearly all of the cities of Cyprus; for instance, a statue of the emperor Vespasian was erected in Salamis by the gymnasiarchs there, but was consecrated by a religious figure. This monument to the emperor reinforces the idea that there was a strong connection between the activities of the state and the pagan cults.

A number of other pagan cults are known to have existed across the island, centered primarily around the major cities of Cyprus. These cities usually had large temples that were dedicated to a specific patron god of the city: in Amathus as in Palaipafos, Aphrodite had her own cult; in Salamis, Zeus Olympius; Pafos contained cults for the gods Asclepius, Hygieia, and Apollo; in Curium, Apollo Hylates. Though these are but a few examples of the many numerous cults, it is important to note that many gods had temples and dedications in many different locations, but not every god is represented. Because Aphrodite is said to have been born from the sea foam around Cyprus, she appears to be consistently worshiped across the island, as evidenced by recurring temples dedicated in her honor. For each of these cults, the method of worship was different; it is hard to say with certainty what each temple did specifically, but we do know from numismatic evidence and literary records that the cult of Aphrodite likely involved prostitution but not blood sacrifice of animals. It is assumed that a majority of these cults followed similar worship services to those found in the corresponding temples in Rome and other locations around the Empire. Despite this assumption, there does not seem to be much evidence to pinpoint specific details surrounding the cult procedures.

While Roman imperial cult maintained significance up until the late 4th century, the ancient pantheon of gods slowly faded out of existence along the way. Following the emperor Caracalla’s death in 217 A.D., inscriptions have nothing more to say about cults such as the Paphian Aphrodite, the Zeus of Salamis, or the Apollo of Hyle at Curium. Each of these cults had enjoyed a long and prosperous history on the island, and, like the imperial cult, seemed to disappear rather suddenly around the 3rd and 4th centuries—the period of Severan rule. All across the island, both imperial cult and the traditional gods began to lack the necessary power to sustain religious faith; after the Roman period, the citizens of Cyprus began to turn to newer, more private gods that were easily accessible and suited to the needs of the individual.

JEWISH REVOLT

Under the reign of Ptolemy I, there was a large exodus of Jews from Palestine to other areas of the Mediterranean. (Hill 241) Their increasing presence on Cyprus most likely occurred due to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD. (Karageorghis 181) A large representation of the Cypriot population, the Jews were also strongly involved in the copper industry. As noted by inscriptions on the construction of a local synagogue, the community of Jews were also possibly on the island to supply wine for the services at the Temple of Jerusalem. (Mitford 1380) With years of building tension with the Romans, during the reign of Trajan in 116 AD, the Jews revolted at Salamis, as well as in Egypt and Cyrene (Hill 242). The most destruction however occurred at Salamis, where there were no stationed Roman garrisons or troops. Led by Artemion, it is estimated that over 240,000 perished in the revolt (Hill 242). Detailed by the writings of Cassius Dio, the Jews brutally massacred every non-Jew in the city. (Mitford 1380) The revolt was quickly quelled by the Roman General Lusius Quietus (Hill 242). All Jews were expelled permanently from the island and even those that were driven there by storm were executed immediately. (Karageorghis 181) Although archaeological evidence suggests that in later centuries the Jewish community was re-established.

INTRODUCTION AND SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY

In AD 45, St. Paul went on his first missionary journey to Cyprus with St. Barnabas, a native Cypriot Jew, and John Mark. Starting at Antioch, they traveled to the port of Seleucia and onwards to Salamis to preach Christianity. As noted in the Acts of the Apostles 13:1-14:27, on their journey to Pafos, Paul and Barnabas encountered the Roman Proconsul Sergius Paulus and a Jewish sorcerer, Elymas Bar-Jesus. Upon hearing Paul’s words, Bar-Jesus was temporarily blinded, and this act convinced Sergius Paulus to convert to Christianity. He was the first Roman governor to do so.

After a quarrel with Paul, Barnabas and John Mark traveled back to Cyprus on his second missionary journey. During his preaching at Salamis, Barnabas was murdered by a group of Jews. John Mark buried him with a copy of the gospel of St. Matthew, which Barnabas always carried with him.

MAJOR BASILICAS AND CHURCHES

The ancient village of Kopetra in the Vasilikos valley contains the remains of three churches dating to the Late Roman period. The first, a small basilica located at the site of Sirmata, dates to around the beginning of the 7th century. The basilica contains a crypt with two tombs. The construction styles of the tombs suggest the second was added later, around the middle of the 7th century. The central courtyard of the basilica was surrounded on three sides by rooms which may have served as domestic spaces for the religious community living there. A cistern had also been cut into one corner of the courtyard. The basilica was close to and yet separate from the nearby village, reflecting the spirit of monasticism in early Christianity. The second church, which was located to the south of Kopetra, was similar in design and proportions to the Sirmata basilica. The remains of a mosaic floor have been found in the sanctuary, although the original subject remains a mystery. The third and largest of the three churches lies to the northeast of Kopetra. The architectural style is similar to the other two Kopetra churches, yet also reflects many characteristics of churches built across the island during the 5th and 6th centuries. The dome covering the sanctuary once held a colorful glass mosaic. All three churches were likely maintained and used until they were abandoned some time in the 7th century.

The basilica of Kourion was built over the remains of the buildings destroyed in the earthquake of A.D. 365. Although its proportions were a little longer than other examples, the basilica was internally similar in architecture to other 5th-century churches and basilicas. The ruined buildings provided all the limestone, granite, and marble needed to build the new church. Remains of a mosaic between the windows in the sanctuary have been found among the ruins. A well-preserved mosaic belonging to one of the previous buildings has been found beneath the floor of the diakonikon. A total of forty inscriptions have been found in and around the basilica, although most remain only in fragments and were only preserved by the reuse of materials after the basilica was abandoned. The earliest inscription dates from the 3rd century BCE, during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphos. The inscriptions dating to the Roman Period on Cyprus include one honoring the proconsul Julianus, and another which mentions the gymnasium of Kourion. The basilica was destroyed by an earthquake in the 7th century. Remains suggest that the building was not immediately abandoned, but was still used until the 8th century.

The Late Roman site of Maroni Petrera is located along the south coast of Cyprus in the Maroni Valley near the modern village of Maroni. The remains of a church have been uncovered at this site as part of the Maroni Valley Archaeological Survey Project (MVASP) founded in 1990. The Petrera church was the religious center for the Maroni valley, yet archaeological evidence of a complex of rooms and courtyards separate from the church indicate that the site was also associated with storage and agricultural production. Recovered remains indicate that the decoration of the church was relatively plain; there is almost no evidence of mosaics, wall-paintings, or the use of marble. Otherwise, the Petrera church was architecturally similar to contemporary Christian buildings in Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean.

ROMAN CYPRIOT BURIALS

Burial customs are typically slow to change, even during times of social transition and foreign influence. Burial customs on Cyprus during the Hellenistic period were largely retained during the Roman period. Nevertheless, the study of these customs can still provide a great deal of insight into who was living in Cyprus at the time and the extent of their influence. The tombs of Roman Cyprus typically were cave-like chambers with sloping dromos, the ends of which were sealed with earth and occasionally with stone. The number, size, and ornamentation of these chambers in differed according to wealth, ethnicity, and the dates of construction. Multiple burials, in which all members of a family shared a tomb, continued to be popular into the Roman period. The typical burial chamber was an elongated rectangle, with side niches or accompanying chambers. Loculi, or rectangular bed-like areas for the dead, were often attached to the chambers, radiating in a symmetrical fashion. Plaques next to loculi with inscriptions of the names of the dead or proverbs in honour of the dead were not uncommon. Epitaphs containing ethnic adjectives, or titles indicating rank or status, have proved helpful in determining the context of certain burials. Identification of the dead was also located on cippi, located directly above the tomb. Cippi are carved-stone altars comprising a base, a narrow shaft, and a cap. Inscriptions labelling the tombs were made on the shafts of the cippi, and other forms of ornamentation (such as foliage) were common. The living could honor their dead by placing flowers on the cippus or pouring libations on the cippus. Gifts continued to be incorporated into burial, as seen in early period of Cypriot history. Jewellery, imported Roman pottery, local imitation pottery, gold wreaths, and glass were common burial gifts. Mummy portraits, depicting the deceased wearing gold wreaths and busts or stelae of the dead, began to emerge as a result of Alexandrian influence. Lamps, cookware, and libation vessels have been excavated in these tombs, suggesting the continuation of funerary feasts of the living during the Roman period on Cyprus.

Tomb structures that are unique or scarcely located are assumed to be those of the elite, or foreign. Uncommon burial practices that occurred during Roman Cyprus included cremation, tumulus tombs, sarcophagi, and peristyle tombs. A multitude of tombs in Nea Pafos, excavated by M. Markides in 1915, represent Peristyle tombs. Peristyle tombs typically had a long, stepped dromos, a long rectangular vaulted room with radiating loculi, and several minor chambers (one located directly behind the other). These are attributed to either Egyptian-born individuals, or Cypriot elite who wished to be buried in the Alexandrian fashion, because Nea Pafos was a significant site of contact with Egypt. Luigi palma di Cesnola and others extensively excavated the site of Kourion. The Roman tombs excavator here were elaborate and highly representative of Roman burial outside of Cyprus. Tomb 8, detailed my George McFadden had a stepped dromos with oblong ashars along the sides. The tomb had a saddled roof, and two large chambers with doorways. The doorways were accented by decorated posts and lintels. The interpretation of the complexity of this tomb is under debate. Another example of a tomb likely belonging to a foreign family is tomb 26 of the Swedish Cyprus excavation in the early 20th century at Amathus. The tomb is an unusual, large, flat tumulus tomb built upon a rock. The tomb has a circular shaft with a stone pithos in middle. Inside the pithos is an alabastron containing carefully washed, cremated bones. Other rare discoveries of Roman-period cremation remains have been found in cylindrical lead urns.

Unfortunately, Cypro-Classical and Hellenistic tombs have been difficult for archaeologists to define because of haphazard excavation of tombs on Cyprus, as with other sites. Looting or treasure-seeking individuals often left tombs in unpreferable conditions, void of archaeological context, making modern research difficult, if not impossible.[40] Additional prime examp les of burials during the Roman period on Cyprus can be observed at the sites of Agioi Omologites – Nicosia, the necropolis at Marion, the necropolis near Skouriotissa, and tombs of Pafos, Curium, Kition, and Salamis.

WOMEN IN CYPRUS

For women on Cyprus during the Roman period, life was restricted mainly to domestic activities. Based on the large amount of epigraphical material from Mesaoria and the southern coast of Cyprus, women did have a part in public life. One-third of these epitaphs are to women. Most of these women mentioned are married to men of status and wealth, or come from wealthy families. This was the most common way for a woman to have a public life. For example, a woman from Salamis, the wife of a Salaminian High Priest of the Augusti, was honored by the Koinon for her public spirit. In addition, a Claudia Appharion, the High Priestess of Demeter for the entire island, was distinguished publicly as well. A woman belonging to a Senatorial family, and a benefactress of Pafos were also honored for their public spirit. Women were mainly left to household duties, but those of particular wealth, or married to men of political or high social status could make a name for themselves. Religion was really the only other avenue left to women to create a public identity.

ART AND CULTURE

GLASS IN ROMAN CYPRUS

Before the invention of glass blowing in the mid first-century BC, glass had been a fairly rare and expensive luxury commodity, the use of which was mostly confined to containers for perfume and cosmetics. However, with the invention of glass blowing, glass became much more widely available and affordable and began to be produced on a much larger scale with factories dedicated to the production of glass being established throughout the Roman world, including Cyprus. Though it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between locally produced Cypriot glass and imported glass in Cyprus, it can be conclusively stated that glass was in fact being manufactured locally within the island. Evidence for this can be found in sites such as Salamis, Tamassos, Limassol and Amathus. A glass workshop was discovered at Tamassos by Ohnefalsch Richter though he was unfortunately unable to fully publish his findings. He does however mention the discovery of a glass furnace which points to glass being manufactured at the site. Although his discoveries were never dated precisely, many consider it likely that they dated to the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD. Blocks of glass were discovered at Salamis which seems to indicate that this was another glass production center though a furnace associated with this site has not yet been discovered. Cypriot glass is thought to have flourished in the Antonine and Severan periods, or from 140 AD to 240 AD and indeed most of the glass discovered is dated to this time. The fact that the economy in Cyprus was flourishing during this period further supports this conclusion.

Olaf Vessberg studied the large quantities of glass found in the tombs of Limassol and Amathus and made several discoveries. First of these was that Cypriot glass is fairly homogeneous. Its function was for the most part limited to daily use, being employed either toward cosmetic purposes or as tableware. The principal shapes being produced by Cypriot glass blowers consisted predominantly of jars, beakers and unguentaria, or flasks that contained oil or perfume. Though it is often difficult to distinguish between beakers and jars, the word beaker is mostly used to describe drinking-vessels while jars are considered to be containers for salves and cosmetics.[48] Distinguishing between the two can often be done through examination of the rim of the vessel which would often be unworked if it was not a drinking vessel. Furthermore, jars often had decorated lids that had a design enamelled on the side facing the interior. Among the unguentaria, there were bell-shaped, candlestick, and tubular. As stated before, many held oil or perfume but some think the tubular unguentaria, named tear-bottles by archaeologists, may have contained the tears of relatives or the deceased. Glass was also being used in Cyprus to produce sack-shaped beakers. These are significant as they are only found in Cyprus. This, and the presence of several defective pieces in Cyprus gives further evidence of glass manufacturing in Cyprus.

CYPRIOT SCULPTURES OF THE ROMAN PERIOD

Roman influence can be seen in the use and import of marble as a medium for sculptures, and the display of these sculptures within civic centers and private homes. This use of marble was limited to economically and politically powerful cities located near harbors such as Salamis and Pafos, where there was easier access to imported marble and means to afford and display these statues. It is unknown whether the marble was carved prior to shipment to Cyprus, or if the marble was shipped as blocks and carved on the island. Although marble was a key part of Roman period sculptures on Cyprus, limestone was still being used for sculptures. The use of limestone has been seen to reflect the easy access, and more likely cheaper material from which to carve from, but it has also been viewed as a reflection of Cypriot art style. Limestone may have been a deliberate choice made by the artist, or buyer, to have a Roman style sculpture carve in Cypriot limestone. This is assumed to reflect the idea of a Roman Cyprus, by combining the Roman art style with the Cypriot limestone. The sculptures discovered on the island do not cover the full Roman style, for example togate figures and busts have yet to be found. There are however many Roman-style portraits, statues, and a few reliefs found on the Island (Vessberg and Westholm, 1956). Inscribed bases attest to the existence of bronze sculptures during the Roman period. The one surviving statue is of the emperor Septimius Severus.

Another key change to sculptures during the Roman period, was how the Cypriots displayed their work. Cypriots had reserved their sculptures generally to sanctuaries, and were not meant for large public displays. This changed with the Roman period, as Cypriots began to move their sculptures into the public eye, and into large urban areas. This allowed the island to show off the grandeur and splendor of Rome, and to honor the Roman emperors.

With the transition to Christianity the older sculptures were modified to reflect Christian values, such as covering or destruction of nudity, or modification of old Greek gods into Christian figures.

Presently, Salamis is the most important city for Roman period sculptures, but Pafos, Kourion, and Soli are also important archeological sites.

EARTHQUAKES

Cyprus is located at the boundary between the African and Eurasian plate, an active margin in which the African plate is colliding with the Eurasian plate. This collision between two plates is the cause for the large magnitude and frequent earthquakes, especially seen in the southern portion of the Island where a portion of the African plate is thought to be subducting underneath Cyprus. Historically Cyprus has been affected by 16 destructive earthquakes, 7 or higher on the modified Mercalli scale, from 26 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Six earthquakes of note affected Cyprus during the Roman period. In 26 B.C. an earthquake with an intensity of 7 with an epicenter located southwest of Cyprus caused damage in the city of Pafos. In 15 B.C. many towns in Cyprus experienced a magnitude 8 earthquake, but at Pafos and Kourion it registered as a magnitude 9. Its epicentre was southwest of Pafos and it left the city in ruins. Pafos was subsequently rebuilt and renamed Augusta by the Romans. The earthquake of 76 A.D. was among the most destructive earthquakes, with a magnitude between 9 and 10, and it was reported to have created a tsunami. Its epicentre was located southeast of Cyprus. Salamis and Pafos took the brunt of this earthquake, and fell into ruin, with other cities such as Kition and Kourion have been assumed to share the same fate due to magnitude of the earthquake. The destructive nature of the earthquakes can also be recorded in the transfer of Roman mint to Cyprus, as a means to alleviate the island from this disaster. A magnitude 7 earthquake that left Salamis and Pafos in ruins occurred sometime between 332-333 A.D.[54] Its epicenter was located east of the island. In 342 A.D. a magnitude 10 earthquake struck Pafos[53] and Salamis, destroying the cities. It may also have changed the course of some small rivers, as well as causing a series of landslides and fault displacements. The final Roman-period earthquake, a magnitude 7 to 8, occurred in 365 A.D. The south coast of Cyprus was greatly affected by the quake, especially Akrotiri and Kourion. A series of earthquakes following upon the initial quake laid waste to Kourion, and marked the transition into Christianity.

CITIES

NEA PAFOS (“NEW PAFOS”)

Nea Paphos officially became a city in 312 BC under Nikokles, the last king of the Pafian kingdom. It wasn’t until the second century that the city grew in importance and became the capital of Roman Cyprus. The earliest account of Pafos as the capital of the island actually comes from “The Acts of the Apostles” in the New Testament, where Paul and Barnabas stayed to preach to Sergius Paulus, who then converted to Christianity. Roman Pafos reached its golden age under the Severan Dynasty (and it is attested that there was even an imperial cult to Septimius Severus). Nea Pafos is not to be confused with Palaipafos (“Old Pafos”). However, it is difficult to separate the two, because they were considered to be the same city under Roman rule, and were connected by “a sacred way”. Nea Pafos was the city center, whereas Palaipafos, where the Temple of Aphrodite was, acted as a religious center.

The temple of Aphrodite at Palaipafos was one of the most important temples in all of Cyprus. It seems that the importance of this religious festival helped maintain the status of the city throughout the Roman period. It is even said that the emperor Titus visited the Temple of Aphrodite at Pafos on his way to Syria. Once there, Titus was awed by the lavishness of the sanctuary and inquired as to his future endeavors as emperor. The high priest and the goddess Aphrodite herself, supposedly, confirmed the ruler’s favorable future and successful journey to Syria.

The temple at Palaipafos was the leading center for the emperor cult. At the beginning of the 3rd century A.D., a statue of the Roman emperor Caracalla was consecrated at Nea Pafos. In the year proceeding, a second statue of the emperor was erected, this time at Palaipafos. Inscriptions at the old city suggest that aside from Aphrodite, only the Roman emperor was worshiped there. Even at the new city, worship was reserved to only a few gods and the emperor. These gods were most likely Zeus Polieus, Aphrodite, Apollo, and Hera. The Sanctuary to Apollo was to the southeast, right outside of the ancient city. It was composed of two underground chambers – a front rectangular one and a back circular one with a dome. This Sanctuary might be contemporary with the foundation of the city. The emperor, on the other hand, was worshiped down to the end of the Severan Dynasty–Septimius Severus—the final emperor who enforced imperial cults.

Imperial cults were not the only way in which Pafos showed its devotion to the empire. In fact, Pafos created a calendar, called either the Imperial or Cypriot calendar, sometime between 21 and 12 BC. This was done to praise Augustus and the Imperial family. It is likely that the calendar was created in 15 BC when the emperor provided funds to rebuild the city after a large earthquake. Although it originated in Pafos, it quickly grew popular and dominated the western and northern areas of Cyprus, and perhaps the southern coast as well. However, it was not the only calendar used throughout the island. The other was the Egyptian calendar used in Salamis, a city who remained loyal to her Egyptian past rather than the empire. Pafos was also given several titles under various emperors. After it was damaged by an earthquake in 15 BC, it received financial aid from the Augustus and the title “Augusta.” The additional name of Flavia, which Pafos bore in Caracalla’s reign (Paphos Augusta Claudia Flavia), was evidently added as a result of the rebuilding of the city under the Flavians after it suffered from another earthquake. It was at this time that the mint was transferred from Syrian Antioch to Pafos. These silver coins, however, were short lived. The city was given the title of “Claudia” in A.D. 66. Pafos was also the favorite city of Cicero, a prominent Roman orator and politician.

The Koinon was a confederation of the various Cypriot cities that maintained political and religious power over Cyprus. Acting as a representative body for all of Cyprus’ cities, the Koinon was likely founded at Palaipafos because the Temple of Aphrodite located there hosted a number of religious festivities which attracted Cypriots from all corners of the island. By the end of the Roman period, the Koinon had gained the power to mint its own coins, bestow honorary titles on important individuals (including erecting statues), determine games and other religious events, and even control politics to a degree. It is unclear when the Koinon began to meet at Pafos, though it certainly occurred by the end of the 4th century B.C. Despite this shift in locations, the old city maintained importance as the center for religious activity on Cyprus for centuries after, up until the end of the 4th century A.D., when the Roman emperor Theodosius I outlawed all pagan religions.

PAPHOS – AGORA

Nea Pafos was located on the western coast of Cyprus, where modern day Kato Paphos now stands. It was among the wealthiest, if not the wealthiest city in Roman Cyprus. The city had walled with towers disposed at regular intervals, and had a harbor (and although it was not of significant size, it was protected by two breakwaters and is still serviceable today). There was also an odeon and a theatre, and two large houses have been excavated. An agora has been found, but only the foundation exists today and excavations are still ongoing. What might have been an acropolis is now covered by a modern-day lighthouse.

PANOODEON PAPHOS

The odeon, although damaged by the hands of quarrymen, has been partially restored. It was a semi-circle and consisted of an auditorium and a stage. It was built entirely out of stone and faced the agora; it was destroyed under the earthquakes of the fourth century. The theatre was built as a result of the urbanization of Pafos. It was located on the northeast corner of the town, built against the southern face of a low hill, and positioned so that the audience could look across the town and in the direction of the harbor. It held approximately 8000–8500 people and was one of the few times the entire community came together. The orchestra was in the flat area between the curve of the seating and the stage building. There is very little left of the stage and the stage building today. The use of the theatre ended in the later part of the fourth century, possibly around the earthquake in 365AD. It was excavated by the University of Sydney in 1995 and a series of exploratory trenches were opened by the University of Trier in 1987.

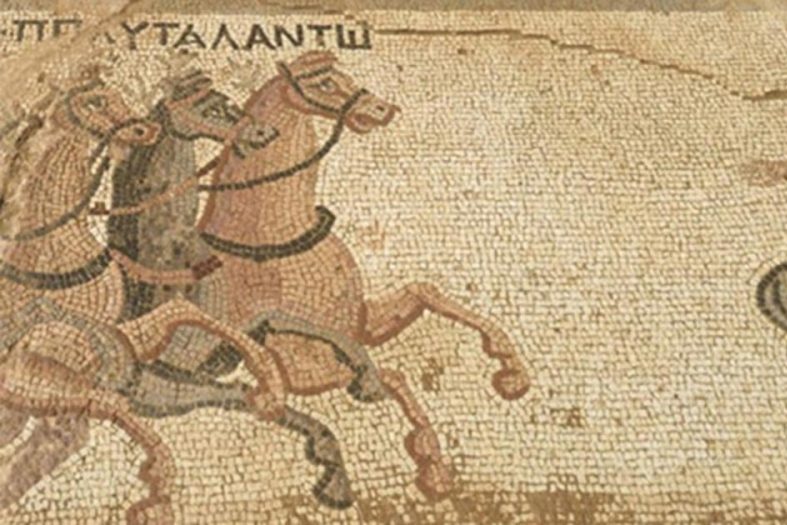

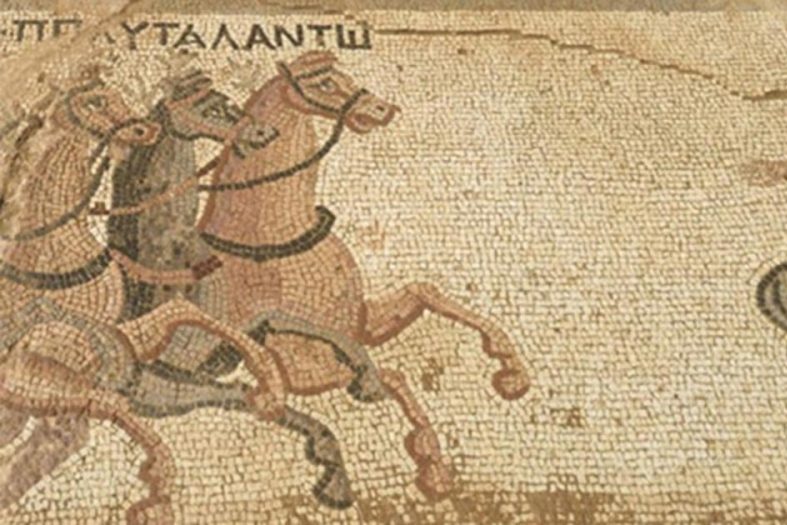

The two houses that have been excavated, the House of Theseus and the House of Dionysus, are both large and luxurious houses, another sign that indicates that Pafos was a very wealthy city. The former of the two, the House of Theseus, was a public building that probably belonged to the Roman governor of Cyprus. It was named after a mosaic of Theseus killing a Minotaur that was found in the house and dates to the fourth century. The house is located a short distance from the northwest harbor. The main entrance is to the east and the principal room is in the south wing, along with the baths. Most of the mosaics have been badly damaged and excavations of the house are ongoing.

HOUSES OF DIONYSOS MOSAIC, PAPHOS

The House of Dionysus, on the other hand, was a private house, probably belonging to a very wealthy citizen. It was given the name because of the frequent appearance of the god on the mosaic floors and dates to the latter half of the second century. On top of the mosaics in the principle rooms, the walls were also decorated with beautiful designs. The bedroom and bathrooms lie in the east wing of the house, whereas the kitchen and workshops lie to the west. Facing the bedrooms to the south is a fish pond “equipped with niches around its bottom in order to serve as a refuge for the fish in hot weather.” Excavations of the house began in 1962.

Hellenistic cemeteries for Palaipafos are found at the south and southwest areas of the city; cemeteries of geometric, archaic, and classical periods found North, East, Southeast of Palaipafos. The “Tombs of the Kings” can be found at the northernmost end of the northern necropolis of Pafos. The tombs themselves are not “royal” but “owe their name to their impressive character.” They date back to the third century BC, but some of the tombs were used in the Early Christian period.

The city suffered severely from earthquakes in the fourth century AD. It was around this time, in 346, that the capital was transferred back to Salamis. Cyprus continued to grow and enjoy several prosperities in the 400s and 500s, but Pafos was already in ruins by this point.

PALAIPAFOS (“OLD PAFOS”)

In Roman Cyprus, Palaipafos was known primarily for the sanctuary to Aphrodite. Palaipafos is located on a limestone hill in southwestern Cyprus, at the mouth of the Diarrhizos river, about one mile inland from the coast. Myth claims that the goddess Aphrodite was born from the sea foam and rose on the rock at the coast called Petra tou Rhomiou. The sanctuary is located a few miles east of the modern Cypriote town of Kouklia, and surrounded, to the west and southwest, by Hellenistic and Roman cemeteries. This sanctuary has one of the longest traditions of cult worship on the island, lasting about 1600 years. Even after the foundation of Nea Pafos in the late 4th century BC, Palaipafos did not lose its significance. It remained a central place of worship in the Mediterranean world and cult worship of Aphrodite continued at this site until the Christian Roman emperor Theodosius I outlawed all pagan worship in 391 AD.

Modern construction in the town of Kouklia has unfortunately obliterated much of the remains at Palaipafos. However, enough remains that Roman built temples can be identified apart from earlier constructions. These buildings are situated on an East/West orientation, and are located in the Northern part of the sanctuary complex. The two buildings, built sometime between the late first and early second century AD, keep to the traditional open court plan for the Paphian cult. It is thought that these were built after the earthquake in 76/77 AD that may have caused some destruction to the sanctuary complex. Reconstructions of the Roman sanctuary show the buildings to surround a rectangular open court, possibly left open on the West side, and enclosed by a South Stoa, an East wing, and a North Hall. The north and south halls are thought to have housed cultic banquets for the goddess. A shrine with an aniconic (non-human form) representation of the goddess Aphrodite was most likely moved from the Old Temple to the new Roman temple. During festivals and celebrations, this conical shaped stone that was a symbol of the fertility goddess was anointed with oils incense were offered. Other religious activities included a procession from the new city to the sanctuary and some form of religious prostitution.

The sanctuary to Aphrodite was one of the primary religious centers on Cyprus. The site was famous and attracted visitors from all over the Mediterranean world. There were many Imperial patrons of the sanctuary and a few emperors even visited the temple, including Trajan and Titus. The importance of the sanctuary is what kept Palaipafos on the map after Nea Pafos was founded. There was a paved road from Nea Pafos to Palaipafos that Cypriots would travel in procession for festivals.

SALAMIS

Salamis, located by the modern city of Famagusta, was one of the most important cities on Cyprus and the eastern Mediterranean during the reign of the Ptolemies. It represents a shift of centre to the north, which coincided with the opening of the ‘south harbour’ at the southern end of the protecting reef—a harbour which was to remain in commission until the flooding of the entire coast-line, possibly in the 4th century. But Salamis, despite this new harbour, was supplanted by Pafos in the early 2nd century BC as the capital of this island; and this distinction, once lost, was not recovered until AD 346, when the city was re-founded as Constantia.

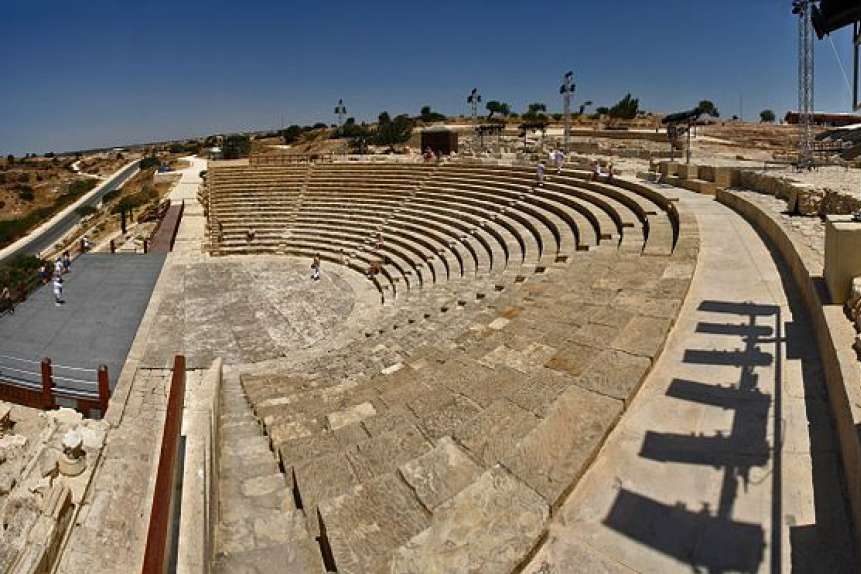

An inscription of the middle Hellenistic date appears to attest to the existence of four gymnasia, which puts Salamis on par with Ephesus and Pergamum. The largest gymnasium, or panegyrikon, which has been excavated, was enlarged during the early Roman Empire by the addition of a bathing establishment and palaestra. Salamis also contained an amphitheatre, also excavated and partially restored, which had a capacity of no less than 15,000 spectators. The amphitheatre, as well as a Roman Bath House, are attributed to the Flavian Ser. Sulpicius Pancles Veranianus. Also discovered at Salamis was a massive temple to Zeus with a ramp constructed in the late Republican or Augustan times and a vast colonnaded agora, which was in use throughout the Roman Imperial period. Salamis, if not the political, remained the industrial capital of the Cyprus, and indeed the most important city on the island.

In AD 22, the temple of Zeus Olympius was one of only three temples in all Cyprus to receive confirmation of its right of asylum. However, there are only eight references, Hellenistic and Roman, to Zeus Olympius, and, as compared with the popularity of the Pafian, the god of Salamis was not esteemed by the emperors and their families. Salamis, unlike Pafos, appears to have been ill at ease with Rome and used, down to the days of Epiphanius, the Egyptian rather than the Roman Imperial calendar. But inscriptions which honor Emperors are by no means uncommon. There are honors accorded to Augustus, to Livia and to his adopted sons; to Tiberius, Nero, Vespasian, Hadrian, Plotina, Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. There is particular enthusiasm for Hadrian, who came to the aid of Salamis, devastated in AD 116 by the Jewish insurrection of Artemion. Salamis shared in the Severan floruit, which is attested by numerous Severan inscriptions, one of which records the erection of a tethrippon to carry the statues of Septimius Severus, his wife and sons. Also during this time, the orchestra of the theatre was converted into a pool for aquatic games. To the west of the city vast cemeteries extended, but, as compared to Archaic and Classical burial, the Roman tombs are conspicuous for their poverty. The Imperial cult was prominent in Salamis, together with the very erratic incidence of Roman civitas. The city received her water under Nero from the famous spring at Chytri, some 24 miles distant, by rock-cut channel and aqueduct.

Salamis was destroyed by repeated earthquakes in the middle of the 4th century AD, but was quickly rebuilt as a Christian city by the Emperor of Constantinople, Constantius II—hence its new name, Constantia. This was a much smaller city than it was previously, centered around the harbor and fortified by walls. Some of the pagan public buildings that lay outside the boundaries of the Christian city, such as the gymnasium and even the theatre, were partly rebuilt, the former as baths and the latter to stage mimic productions.

KOURION

Kourion, located on the Southern coast of Cyprus and protected by cliffs on the north and east, was a walled acropolis with a necropolis to the southeast, and a well-preserved stadium and the sanctuary of Apollo Hylates in the west. However, it is said to have made “no palpable impact upon the Roman world of its day”. We know most about this city through the many inscriptions found on the site and through the excavations of two large residences, the House of Achilles Mosaic and the House of the Gladiators.

Inscriptions found in Kourion have been an invaluable source to the study of Kourion. They are important as they tell us about the various building projects conducted in Kourion under the Romans and the involvement of various emperors. They even provide a record of several of the proconsuls in Kourion and their achievements. They give us insight into the Neronian restoration, repairs done to the Hellenistic theatre under Augustus, the remodelling of the theatre into a hunting-theatre under Caracalla, and other important events in the city. Kourion has a fair number of inscriptions on statues of important figures during the Roman period, including Nero, Trajan, and various proconsuls. There are also a few plaques in honour of Caracalla, Septimius Severus, and other important figures. Inscriptions in and around the Sanctuary of Apollo detail the stages of construction and improvements made to the Sanctuary. Several defixiones, or curse tablets, have also been found at Kourion, often targeting other citizens over legal disputes and of a sufficient quantity to distinguish Kourion from other sites. Several funerary inscriptions left by relatives of the dead were also found although these were not particularly common in Kourion.

The Sanctuary of Apollo, located approximately 1.5 km (1 mi) west of Kourion[70] was a significant feature of the city, being described as the most impressive cult-centre in Cyprus. It is thought to have been built around 65 or 66 AD, during the reign of Nero and would have undoubtedly been destroyed by the massive earthquake of 365 AD. It was first discovered and excavated by Louis Cesnola, whose account of the site proved invaluable as it was later plundered and devastated by stone-seekers. Though Cesnola mentions the presence of columns in his account, none were found by later excavators. The temple would later be rediscovered by George McFadden, whose greatest impact regarding the study of the sanctuary of Apollo was his discovery that the temple had two phases, one Hellenistic and the other Roman. However, the most significant contributor to the study of this temple would have to be Robert Scranton who made many notable findings. It was he who suggested that the temple was never completely rebuilt but instead had its front remodelled, interior divided, and floor level raised under the Romans. Though there is still some debate regarding the exact dating of the temple, many believe it to have been constructed during the reign of Nero. This is supported by the fact that the Neronian period was a time of relative prosperity in Kourion as attested to by the fact that the Theater of Kourion was rebuilt around 64 or 65 AD, only a year or two before the construction of the temple.[70] Overall, it seems that the temple was modernised under the Romans but no dramatic changes appear to have been made. Flowing water (provided to the temple and the city during the reign of Claudius) and a tighter organization of the space constitute two examples of Roman modernisation of the temple. The temple also seems to have had strong Near Eastern connections, evidenced by coins, architecture, and pottery. Because of Kourion’s association of Trajan as Apollo Caesar with Apollo Hylates, he contributed to the building of several structures including the Curium Gate, SE Building, the Bath House, S Building, and the NW Building, as indicated by inscriptions bearing his name.[69] However, after his death worship of Apollo Caesar ended.

The House of the Achilles Mosaic, with its open courtyard surrounded by rooms on both sides and colonnaded portico to the northeast, was dated to approximately the first half of the fourth century AD and is most notable for the large mosaic depicting the famous Greek myth in which Odysseus, by sounding a false alarm, was able to fool Achilles, then disguised as a woman, to reveal his true identity, thus bringing about his participation in the Trojan War which is famously described in Homer’s Iliad. The building had mosaic floors, one of which, although damaged, seems to portray the Trojan prince Ganymede being abducted by Zeus.[71]

More is known about the other famous residence, the House of the Gladiators, which was located in close proximity to the city wall and several meters east of the House of Achilles, seems to have been the residence of a fairly affluent patrician. This house is dated to the second half of the third century AD, apparently having been built prior to the House of Achilles. It consisted of a central courtyard with corridors lining all four walls. The rooms open directly into these corridors. The floor was once covered with mosaics, with cisterns underground to collect rainwater. The house unfortunately did not escape the devastating earthquake of 365 AD unscathed. The walls, roof, and mosaics were all severely damaged. Located in the central courtyard is a mosaic, remarkably preserved, depicting a gladiatorial combat scene, This is significant as such scenes were extremely rare in Cyprus. Only two of the three panels depicting this scene survive unfortunately.

The theater, which was built in the northern part of the acropolis and excavated by the Pennsylvania University Museum from 1949 to 1950, was renovated under Roman rule sometime around 100 AD and once more around 200 AD. Though the auditorium was originally a fully formed circle, under the Romans it was reduced to a half-circle. Around the second century AD it was enlarged to its current size and several buttresses were added to support it. Around 200 AD, it was remodeled to accommodate hunting and gladiatorial games, only to later be converted back into a traditional theater around 300 AD. It is thought to have accommodated somewhere around 3500 spectators. The theater appears to have been abandoned sometime during the fourth century. It still stands today but suffered much from stone-seekers.

The stadium, also excavated by the Pennsylvania University Museum, was located in the northwestern region of Kourion with its U-shaped foundation and three entrance gates still standing today and remarkably preserved. It is thought to have been built around the 2nd century AD under the Antonine emperors and remained in use until around 400 AD. It likely accommodated around 6,000 spectators and consisted of a long oval race track for runners and chariot races. An account can be found of its last race and destruction, provided by a Cypriote writing a fictional account of the Life of St. Barnabas in the fifth century.